Before the invention of photography, the only way to know what places and people looked like was through the interpretative filter of painters. Photography conveyed pieces of reality as it is.

Many photographers used this medium in order to raise awareness to social injustices, by giving visibility to the invisible.

Prominent among them were Diane Arbus, who photographed disabled and mentally retarded people, Lewis Hine who photographed child laborers in factories, in order to raise public awareness to social conditions among the working classes, Nan Goldin who photographed her friends dying of AIDS, Robert Mapplethorpe who photographed black masculine nudity.

I observed the photographs, studied the works of these and other photographers. I saw how their work affected social perceptions, how it set public debate of issues that had not been discussed previously,

These photographers served as my inspiration: it brought about the idea to photograph women who had been sexually assaulted staring into the camera. I called them Heroines.

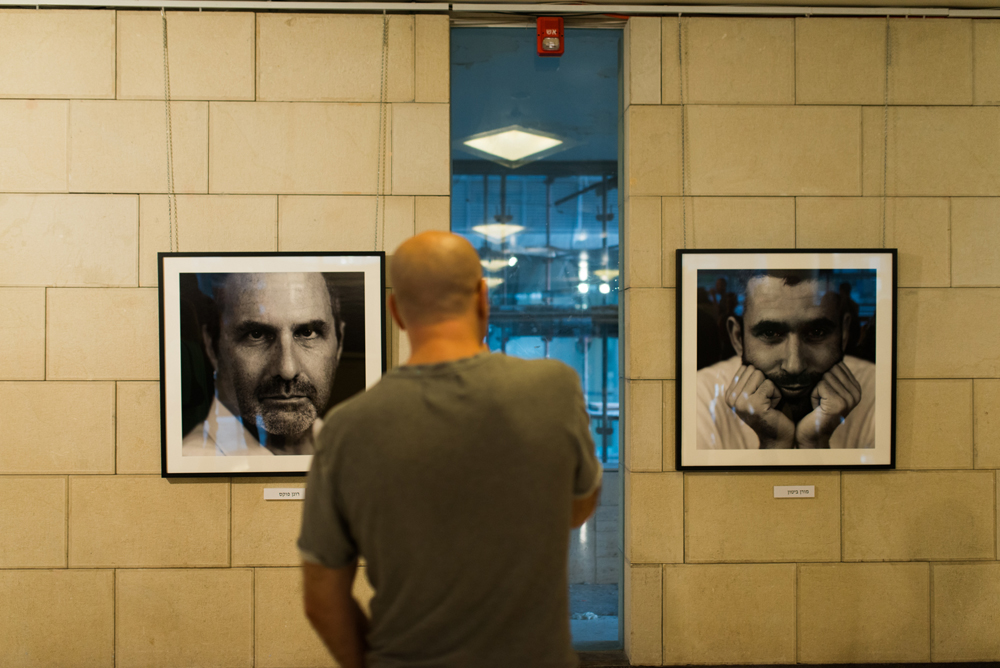

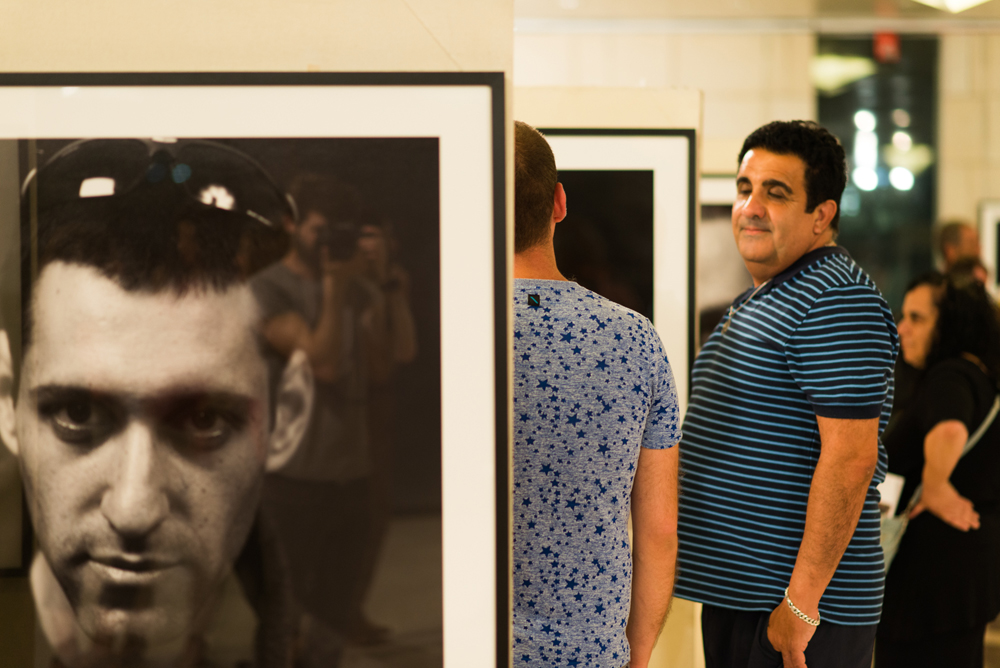

The exhibition “Heroines” was first shown in 2012 and over the years featured throughout Israel, including the Knesset.

It was the first exhibition featuring women who had undergone sexual

assault facing the camera full on, large scale, impossible to ignore.

The exhibition contributed greatly to raising public and social awareness to the issue of sexual assault, first and foremost the women who had made the decision to be photographed: with the exposure, the sense of shame receded. The voice of the heroines was heard, empowered other

women who had been fearful or ashamed, and helped them make their own voice heard. I saw how society started to react to the exposure, how stunned it was by the extent of the phenomenon.

Three years after the first exposure of “Heroines”, I decided it was time for the voice of the men to be heard.

Through my meetings with men who agreed to be photographed, I discovered that the conspiracy of silence surrounding sexual assault of men is so intense, it is like a ring suffocating their soul and body.

The dimensions of the shame, fear and silencing surrounding this phenomenon are horrific.

I sought a turning of the tables: from being an object upon which horrid, inhuman, unconsented acts are allowed to be executed, to become a subject, a unique and distinctive person with his own expression, utterance, personality, name, family.

A whole life to live.

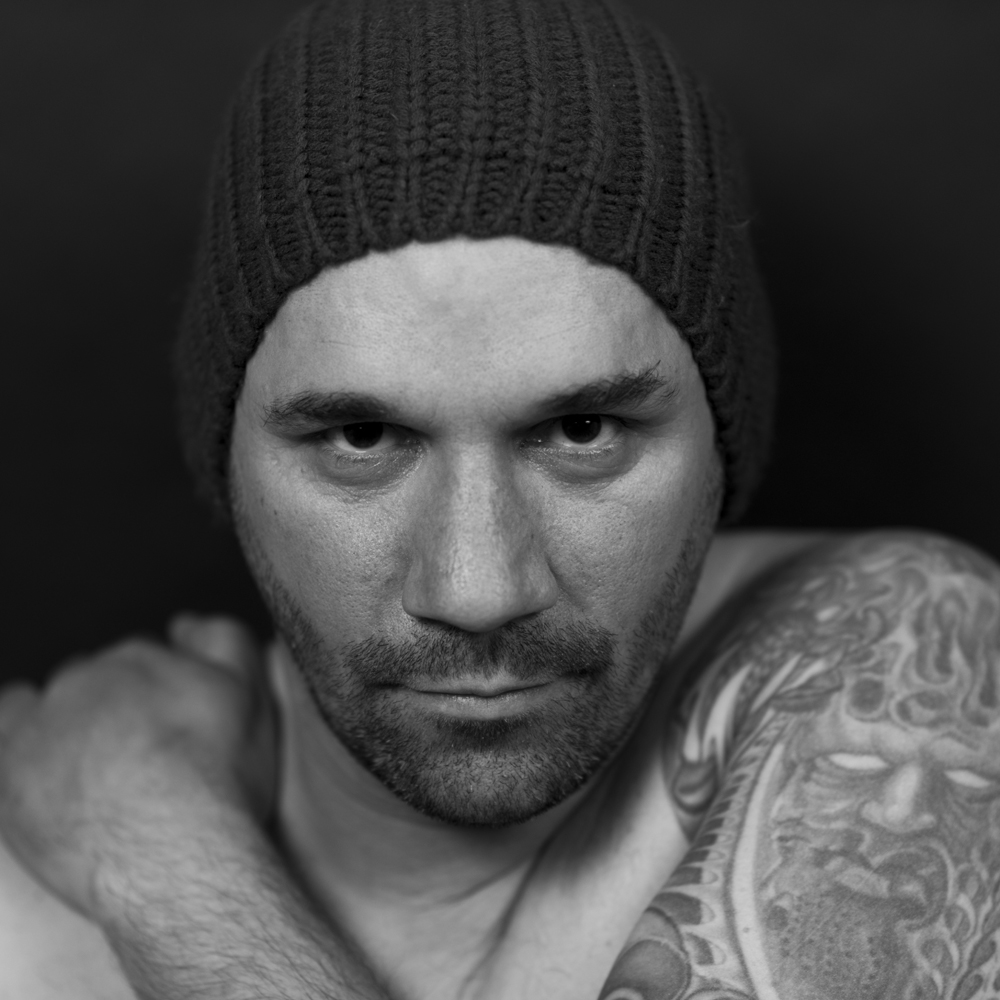

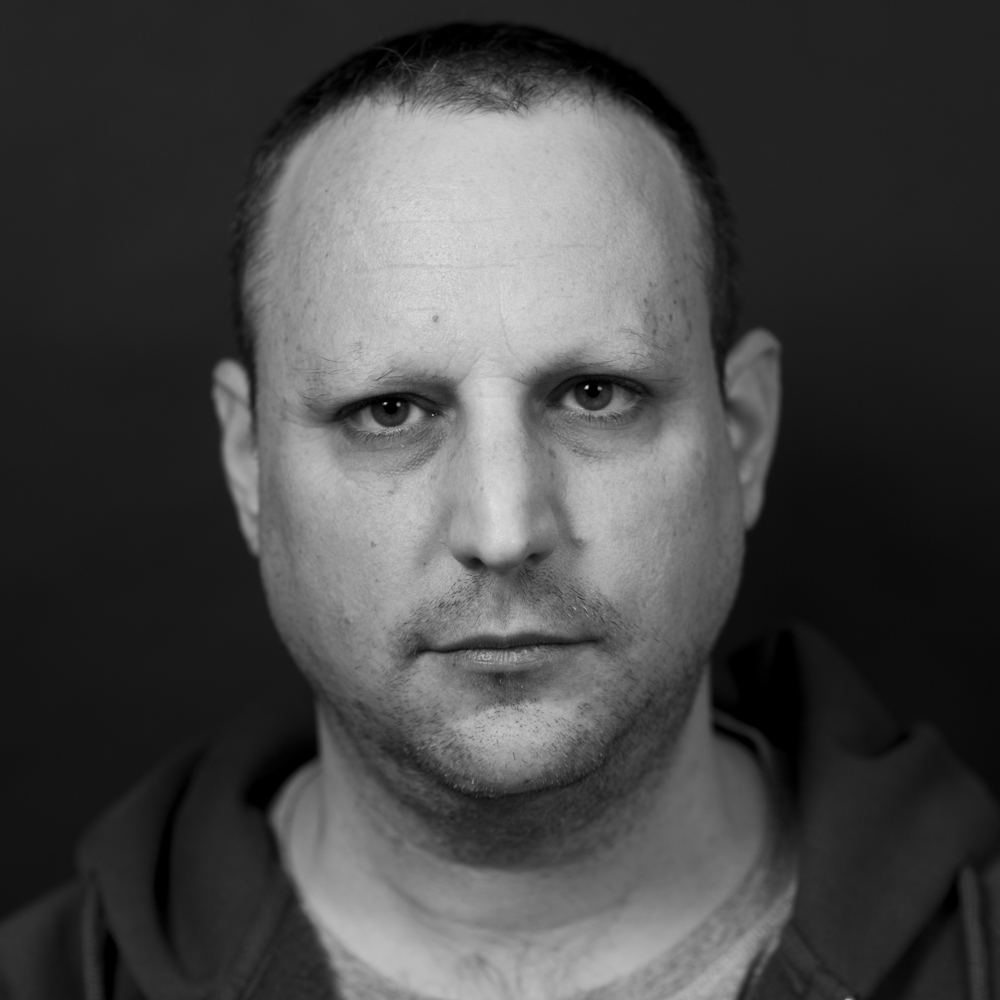

The close, intimate photography invites the viewer to look into the eyes of each of the photographed men, to come closer, become acquainted with them, hear their voices.

The choice of black-and-white photography is not unintended. In the absence of colour (which attracts atention greatly in reality), the eye is more focused on detail: the expressions, the gestures, the face, the watchful eyes.

I therefore sought gestures, a look, something that sets each person aside, which would bring the essence of the man into the photograph.

This series of photographs contains no stereotype of a sexually assaulted man—because there is no such thing as a stereotypical sexually assaulted man.

They are Avi, Avidav, Eran, Erez, Eyal, Hagai, Lior, Meni, Maor, Matan, Menachem, Moran, Nachum, Or, Oren, Ronen, Tal, Uri and Yoel.

Each of these men stands with his head held high, facing me, facing society, and says aloud: I am here, look at me.

Exhibiton catalog: nirim_catalog

Alicia Shahaf

צילומים מפתיחת התערוכה במרכז ענב בתל אביב, 23 ליוני 2016

צילום: דור שחף